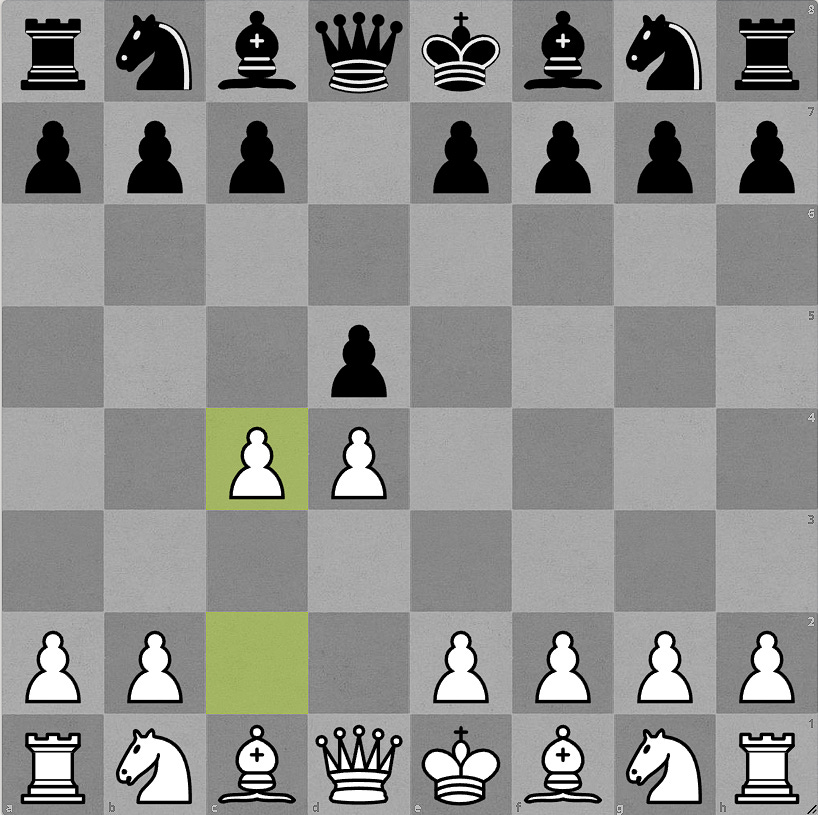

The Queen’s Gambit happens when both white and black move the pawn in front of their queen two squares, and then white moves the queen’s bishop’s pawn two squares. In this position, white could take black’s pawn next turn, but right now, it is black’s turn, and they must decide what to do.

Black must make a choice between accepting the gambit (which means sacrifice) or declining it by making a different move and not capturing it. Usually, black will defend their pawn with another pawn. If they move their king’s pawn in one space to add defense to their queen’s pawn, it is called the Queen’s Gambit declined. If they use their queen’s bishop’s pawn, it is called the Slav defense.

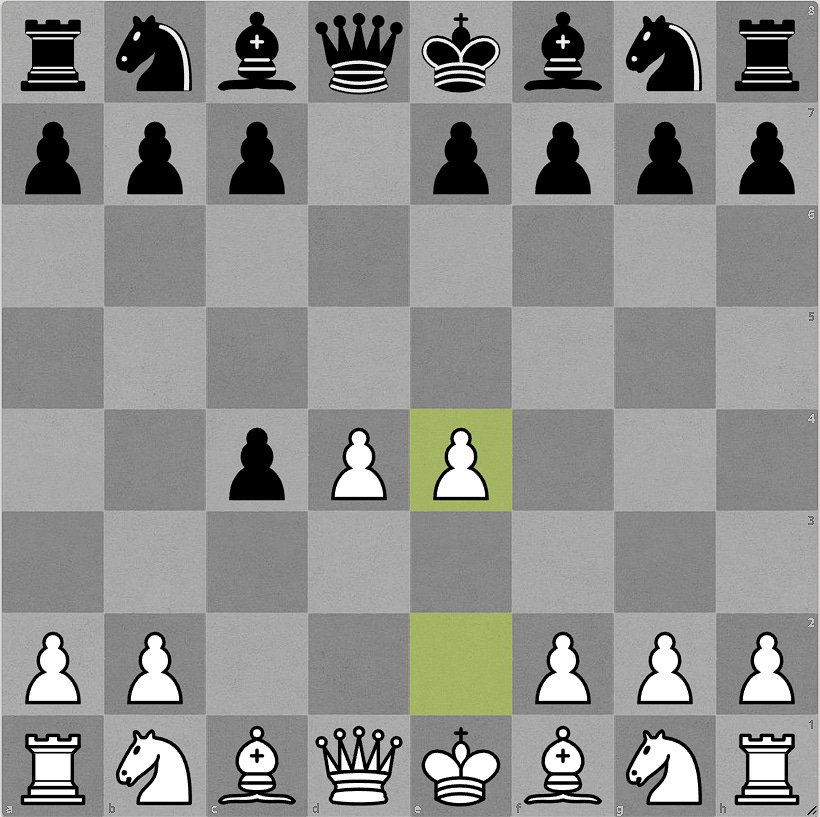

In the next two pictures, I will show you two very common results that could happen depending on what black does and what my suggested response is for white. In the first case, if black captures the pawn, the best move for white is to move the king’s pawn two squares forward. This move means that next turn, white will be able to capture back the black pawn and move the bishop onto its square. The second reason for moving the king’s pawn is to get it out of the way so that the queen has another diagonal direction that she can move in.

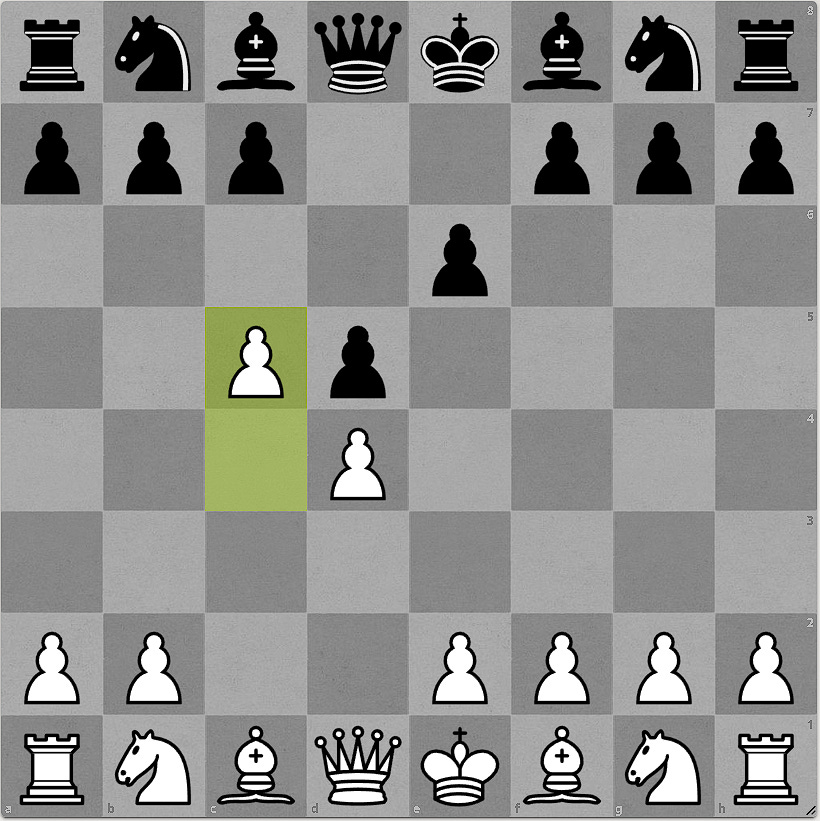

But sometimes, black declines the gambit and defends their pawn by moving their king’s pawn one square. When this happens, my favorite move is to move the pawn that black declined to capture one square forward. What this accomplishes is that both of black’s bishops are trapped by pawns! By slowing black down, white has more time for flexibility as they move out their pieces and plan their attack!

Notice that I didn’t use any chess notation in my explanation so far? That’s because this opening is simple enough to describe without it. However, chess notation is extremely valuable for recording long games in a portable format that chess programs and websites can play back.

For this reason, I will include the chess notation for a game in which white checkmates black extremely quickly!

1. d4 d5 2. c4 dxc4 3. e4 Nc6 4. Bxc4 e5 5. Qh5 Nxd4 6. Qxf7#If you copy and paste that in the analysis board on lichess.org or chess.com, you will be able to replay the moves and see what happened. What happened is that black got so excited about capturing a pawn with the knight and then planning to fork white’s king and rook that it failed to notice that white was setting up a checkmate. Sometimes a game really can end this quickly if your opponent is not familiar with your attacks!

I am still figuring out the technical details of how to include information when I make a book of my posts. For now, all content will be hosted on this blog. This means that all kinds of links can be shared that wouldn’t work in a paperback book.

Check out this video on the Queen’s Gambit that I made specifically to go along with this chapter!